Global diplomacy is no longer complicated by armies, sanctions, and formal treaties. In this time of anemic information ecosystems, mass migration, global health shocks, and situations linked to insecurity through climate change, the power of influence increasingly flows through attraction, reputation, standards-setting, technology partnerships, education, media, and the ability to frame “what is normal” in international life.

This is where soft power has ceased to be a useful addition to hard power and has become a central currency in contemporary international relations. The shift is not an emotional one; it is strategic. States are discovering, sometimes the hard way, that coercion can be useful only for obtaining compliance, but it seldom results in sustainable legitimacy. Legitimacy is what glues coalitions together, attracts investment, builds partnerships, and reduces resistance when crises arrive.

Soft power, according to the most greatly cited definition, means the power to: Influence the preferences of others through attraction rather than coercion or payments. Joseph Nye’s basic insight was not that hard power is outdated, but that the sources of influence have become more diversified as global interdependence intensifies and flows of information accelerate. Under such conditions, the power to persuade, to set the agendas, and to be recognized as legitimate can produce results that can be achieved by no certain force.

Nye’s early conceptual work argued that states can get what they want by making others want what they want, as the attractiveness of cultural, political values, and foreign policies is perceived as legitimate or morally authoritative. The contemporary relevance of this argument can be seen in the fact that states today compete in various ways over narratives, public diplomacy, education, technological ecosystems, and development partnerships, treating these as strategic terrain rather than a “nice-to-have” addition.

If soft power is about attraction, then measurement becomes part of the struggle. Nations are concerned with rankings, global perceptions, and brand reputation because those perceptions influence tourism, investment, talent flows, alliance credibility, and room leaders have to maneuver internationally. One of the most comprehensive modern attempts at quantifying this is Global Soft Power Index, which ranks all 193 UN member countries based on international perception surveys of over 170,000 people across 100+ markets.

The logic behind such indices represents so much more than obviously denouncing the extent of difficulty being gauged by such metrics – it reflects a deeper truth: Whether one believes in every single metric or not, states have increasingly treated reputation as a strategic asset to be built, lost, repaired and converted into diplomatic leverage.

The argument is not that soft power is replacing hard power. Rather, it is becoming increasingly important in determining whether hard power can be applied politically, whether partnerships form that can stand the test of time and if there is acceptance by global publics of a state’s claims to lead. Even strong states may discover their coercive instruments blunted in the face of legitimacy crises, loss of popularity, or distrust across the world.

Read More: The American Dream and Soft Power

On the other hand, states that may not have overwhelming military reach can still influence results through credibility, cultural appeal, mediation roles, education diplomacy and development partnerships, which match recipient needs. That is why the conversation on soft power has moved from usual abstract theory to day-to-day policy: Governments are investing heavily in cultural institutes, scholarship programs, media outreach, digital diplomacy, sports diplomacy and infrastructure diplomacy because they provide pathways to influence that often come with a lower cost than outright coercion.

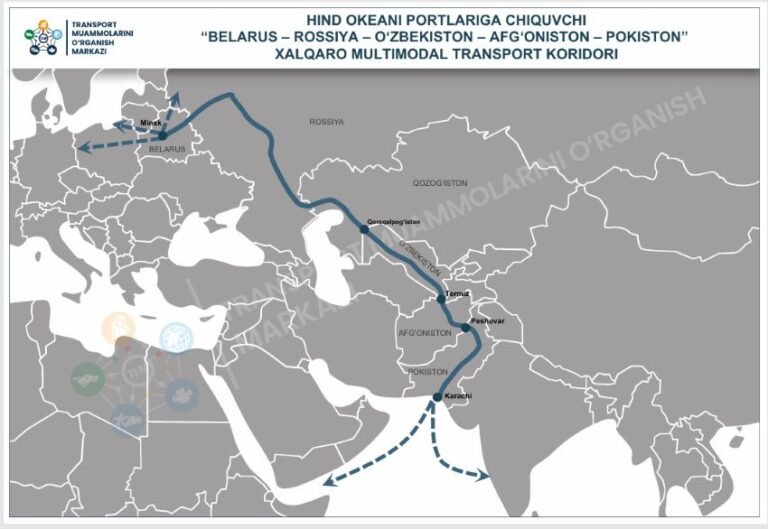

One of the main phenomena of modern international relations is the explicit geopolitical nature of the soft power contest. The European Union’s Global Gateway strategy, for example takes the form of an offer, not just of development assistance, but of “sustainable and trusted connections” aligned with EU values and standards. In a world where infrastructure and connectivity decide trade routes, supply chain resilience and digital dependence, such initiatives are as much about strategic messaging as economic policy.

The EU has publicly endorsed lists of flagship projects for 2025 in different areas, from digital, climate and energy, transport, health, education to research (which suggest connectivity has become part of diplomatic identity and international competition). Reuters has reported that the EU leadership has deliberated on mobilizing more than 400 billion euros of investment by 2027 for Global Gateway, and supports it as a strategic alternative to rival global investment strategies, as part of a broader bid to decrease dependence in critical sectors.

Whether one applauds or critiques this approach, there is no disagreement about the principle underlying it all: Large-scale investments and standards-based infrastructure are now a way to influence global diplomacy based on attraction, partnership stories, and institutional alignment.

China’s contemporary diplomacy is also a creative example of how soft power has developed beyond culture to encompass governance stories and messaging on international public goods. Chinese official communication increasingly highlights the global initiatives of positioning China as a provider of development, security cooperation and civilizational dialogue, presenting its diplomatic posture as constructive and order-making. These initiatives are not just rhetorical, but they are intended to “anchor networks of political relationships, frameworks of cooperation and normative language with respect to global governance.”

At the same time, modern soft power competition is inextricably linked with technology diplomacy. As extensively and thoughtfully reported in Reuters on China’s widening space partnerships in Africa, such cooperation on satellites and ground station access provides some of the finest examples of how science and technology cooperation can act as a steady effort strategy not just in forming dependency but in fostering dependence on the training, hardware, data ecosystems, and institutional partnerships. This is soft power in a more modern guise: Not mere ‘likability’ but strategic embeddedness through capacity-building, infrastructure or perceiving benefits from working together.

One reason soft power is becoming increasingly important is the multiplication of global audiences. Diplomacy no longer takes place solely between governments behind closed doors. It occurs in the social media feeds, diaspora, and in the universities, corporate boardrooms, humanitarian networks and entertainment industries. The foreign policy function is described in terms of public diplomacy categories. Public diplomacy, which used to be a specialized arm of foreign policy, has become a frontline instrument.

Read More: Soft Power: An Obstacle to Chinese Rejuvenation

This transformation brings opportunities and vulnerabilities. Disinformation campaigns, “sharp power” tactics, and weaponized narratives can erode trust in institutions and polarize societies, making it harder to build coalitions and make things diplomatically legitimate. The Soft Power 30 project, a project produced in conjunction with the USC Center on Public Diplomacy, linked explicitly to the measurement of soft power both objective national resources and international polling, to capture the centrality of perception in the modern era of influence.

Even though this report was written before the most recent technological changes, the report’s larger message is more timely: The struggle for influence always rests on how audiences interpret information rather than on what governments want to convey.

Soft power also functions through standards, models of governance, and institutional credibility. A country which is perceived to be stable, predictable and rule consistent tends to have more access to partnerships, investment and leadership roles in multi-lateral settings. On the other hand, reputational harm may limit diplomatic maneuvering space. In this sense, domestic governance is not separated from international influence and is part of the machinery of attraction.

Political values, the treatment of minorities, perceptions of corruption, press freedom and legal institutions credibility can all affect international rating. This is not to say that global audiences agree on a single model of “good governance,” but it does mean that credibility has become a strategic resource that states actively manage and fight over.

Another significant field in which soft power is increasingly shaping global diplomacy is humanitarian and development leadership. States and international organizations use aid not only as a tool of relief, but also as an expression of responsibility, reliability and orientation towards partnership. Yet this is where ethics and morality intersect most visibly with strategy. If the aid is seen to be conditional, self-serving or to obtain political concessions for giving it, it can be counter-productive and undermine exactly what it seeks to attract.

Recent debates in Europe on the foreign policy and strategic orientation of aid and investments illustrate the problems of entanglement with geopolitical competition and migration politics, unfolding in development policy and raising doubts on whether “values-based” diplomacy is being continued or repackaged. Soft power, in other words, is not so much about resources; but about the interpretation of resources by recipients and observers. Differences between being seen as a partner or as a manipulator can make all the difference between influence building or crumbling.

Cultural diplomacy is indeed one of the most visible faces of soft power, but it is also changing. Film, television, music, sports, and digital platforms influence people’s perceptions to a degree more often achieved only through traditional diplomatic messaging. Once a culture becomes globally-konsumрыв it may elicit familiarity and emotional resonance which creates less psychological distance and softens political enmity. This is why states spend money on cultural industries, host international festivals, support language programs, and even promote tourism brands.

Read More: Soft Power Diplomacy: A Case of Pakistan-Ireland Relations

Yet cultural soft power is not always under government control. Cultural appeal can increase through private sector creativity and diaspora networks but can also be adversely affected by political crisis which leads to boycotts, backlash or fall in reputation. The relationship between state strategy and cultural attraction is thus complicated: while governments may help reinforce it, they cannot entirely construct authenticity, nor will authenticity determine whether a cultural export is accepted as a symbol rather than merely viewed as propaganda.

The theoretical framework for soft power helps understand these dynamics and avoid the risk of treating the concept as a vague substitute for “good image”. At core the soft power theory proposes that influence can be created through attraction based on culture, values, and legitimate policy and influence attraction can frame the preferences of other players without using force and bribery.

Nye’s larger work also, however, stressed that power was relational and contextual: different situations rewarded different instruments and the “best” strategy often involved some combination of hard and soft tools that became what in later debates became called “smart power”. From this viewpoint, soft power does not imply passivity and can be a methodical strategy for agenda-setting, narrative framing, coalition-building, and institutional design. A state that takes the lead in setting global norms – be they around climate, trade standards or digital governance, or public health is setting the structure of choices faced by others, which is a form of control that can outlast immediate crises.

Soft power theory also helps us understand the rising levels of competition in the legitimacy field among global diplomatic forces. In many instances, the states would like to ensure that their policies are presented as compatible with universal values or global public goods, because legitimacy may reduce resistance and broaden the sphere of cooperation.

The EU’s description of Global Gateway as “trusted” and “sustainable”, with values and standards at its foundations, is not just sales copy; it represents a claim to legitimacy in the infrastructure and investment space. China’s focus on initiatives centered on developmental goals, security, and civilization dialogue is also feasibly viewed as an effort to produce legitimacy by constructing alternative stories about global order and partnerships. In both instances, soft power is being deployed to define what “responsible leadership” appears to be and shape how third countries perceive the possible options available to them.

But it is important to recognize the limitations and dangers of soft power. Attraction can be easily ruined through perceptions of hypocrisy, inconsistency or coercive behavior dressed in the garb of morality. A state can foster values abroad and then violate them at home or provide a “partnership investment” but extractive deals. In cases like this, the credibility gap can lead to backlash, low influence and create openings for competitors.

This is why modern soft power contests also increasingly involve battles over credibility as such. States do not just sell their virtues; they try to delegitimize their rivals by exposing their contradictions, pointing out injustice, or presenting their policies as exploitative. In this environment, soft power becomes an asset and arena of battle.

Read More: Joseph Nye Who Introduced the World to ‘Soft Power’ Dies at 88

The emergence of digital diplomacy has increased this contest. Social media channels and online groups may spread stories so quickly that they result in overnight blows to reputation or surges of support. Public diplomacy is no longer a one-off to improvise messaging, but a resilience against disinformation, fast responding crisis communication and long-standing communication with the foreign public.

The Soft Power 30 talk of digital dynamics, although written for a different moment, foresaw what would become a reality now: digital square was going to become central to public diplomacy and States were going to need to work through the tension between openness and manipulation. Today, that is reflected by the way states invest in international broadcasting, digital engagement teams, influencer networks and strategically directed communications targeting global audiences.

Another modern aspect of soft power is the struggle for “connectivity” and dependence. Infrastructure diplomacy – railways, ports, digital networks, satellite systems, energy corridors – has an impact on the way countries trade, communicate, and govern. When a state or bloc supplies the infrastructure and standards that others rely on, they will enjoy long term influence that is not easily reversed.

The EU’s approach to investment and China’s approach to technology and infrastructure partnership is part of the convergent overlap between the use of soft power and economic statecraft. This is not force in the traditional military sense, but it can influence choices, alignments, and policy space, mostly for smaller states that desire development but would prefer not to be strategically vulnerable.

Soft power is also important, as most international issues are now solved through cooperation. Climate change, pandemics, cyber threats, financial instability: there are no problems that a unilateral use of force can solve. States perceived as reliable partners and responsible contributors can gain influence out of proportion to their military power. States seen as disruptive or unreliable, on the other hand, can be isolated, or even resisted if they accumulate formidable hard power. The soft power contest, therefore, is not just about popularity; it is about how to create the level of trust and legitimacy to collaborate.

In this sense, the increasing power of soft power is changing the face of global diplomacy as a struggle over the narratives of order. Competing visions of development, governance, security and modernity are being offered in the form of diplomacy, investment, technology partnership and cultural projection. The EU’s formulation of “trusted connections” and China’s focus on international initiatives are two visible ends of the contest, but they are not the only ones. Middle powers also invest in the diplomacy of mediation, humanitarian branding, education exchanges and institutional building in the region to boost their stock and leverage. The diplomatic stage becomes one or groups with endogenous relations built upon trust, compatibility in standards and feelings of competence.

Read More: What is Panda Diplomacy and How China Uses Pandas as a Soft Power Currency?

The crucial policy implication is that soft power must be sustained over a long period of time. It is taken a long time to build through credible institutions and reliable partnerships and constant engagement, but it can be damaged very quickly through apparent hypocrisy, sharp policy reversal or a crisis that shows weakness of institutions. Funding cut-backs on development and humanitarian programs, for example, can not only have consequences in terms of immediate suffering, they can also reshape world perceptions of reliability and moral leadership. Similarly, aggressive rhetoric or coercive measures can undermine diplomacy’s ability to attract other states to its principles by driving them toward an alternative.

The rise of soft power does not herald the demise of hard power, but it does mean that coerced power (without credibility) is becoming more expensive. Modern diplomacy is not only influenced by what states can enforce others to do but what they can convince others what is legitimate, beneficial and consistent with common interests. At its best, soft power is the capacity to make cooperation feel natural or to make leadership seem trustworthy.

At its worst, its a branding exercise that under the weight of contradiction, crumbles. The central challenge facing modern states is thus not just to “increase” soft power, but to reconcile the relationship between domestic forms of governance, foreign policy behavior, and international linkages in ways that demonstrate the politics of attraction (rather than strategic cynicism).

In a world where audiences are quick to judge credibility globally and where strategic competition increasingly is fought on perceptions, soft power has become one of the most important tools of influence. It influences who sets the agenda, who forms the leaders of coalitions, whose standards are internationally accepted, whose connectors are considered an opportunity and not dependency. The molding of global diplomacy in the twenty-first century is thus inextricably linked to the increasing sway of soft power – not as a fashionable concept, but as a structural fact in international relations.

*The views presented in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Diplomatic Insight.

Atiqullah Baig Mughul

Atiqullah Baig Mughul is a graduate in International Relations, specializing in security studies, Middle East politics, diplomacy, and policy-oriented geopolitical research. He can be reached at atiqullahmughal18@gmail.com

- Atiqullah Baig Mughul

- Atiqullah Baig Mughul

- Atiqullah Baig Mughul