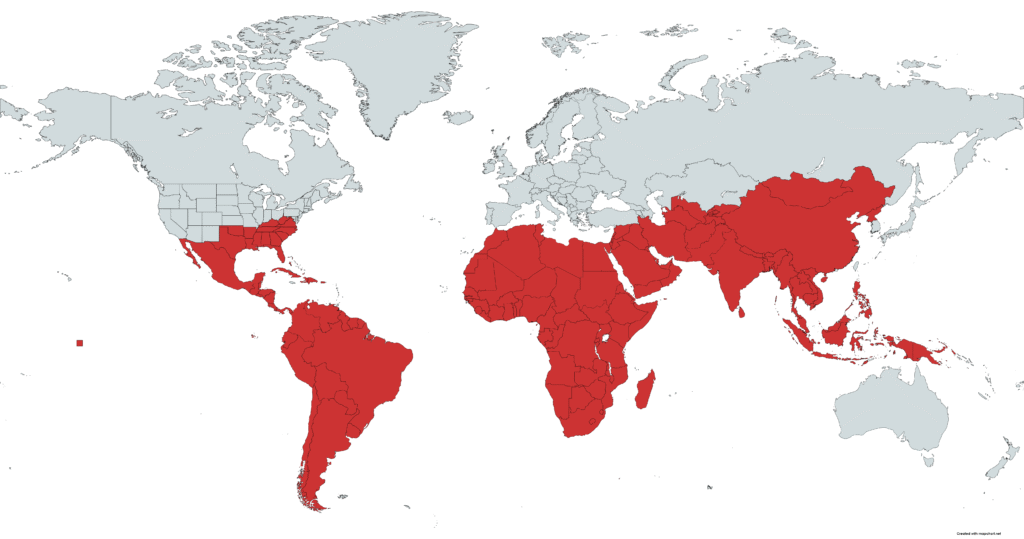

While global climate justice often focuses on the Global North’s responsibility, an equally urgent yet underexamined deadlock lies within the Global South: its failure to mobilize as a unified, justice-oriented force. South-South cooperation, an ambitious postcolonial solidarity, exists as a fragmented action despite having global players like China and India. While they have the capacity to lead, their minimum focus on collective responsibility and intentional favor for geopolitical interests effectively sidelines the vulnerable countries.

South-South cooperation needs to be a political and structural counterweight to position itself more effectively in the global climate regime, which is currently dominated by the Global North. Its involvement as a rhetorical solidarity and conventional aid allocation urges holistic transformation. Apart from dismantling external dependency and internal hierarchies, climate justice will remain only a moral aspiration. It is time to justify reforming South-South cooperation, whether to adapt the current order, or function a new justice-centered global climate architecture.

The Structural Problem: Why the South Cannot Just Negotiate

From the design of carbon markets to conditional climate finance, the Global North has been dominating the architecture of global climate governance for decades. Under this hierarchy, the South adapts while the North controls. Framing donor-recipient logic, North controlled financial institutions (e.g., World Bank, IMF, GCF, even USAID) produce further injustice, limit autonomy, and entrench structural dependency.

Moreover, the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and Loss and Damage (L&D) mechanisms become political instruments of the Global North to impose Northern structural accountability. The Global South conditionally accepts and remains reluctant to the donor-concentrated climate technologies, patents, and intellectual properties, perpetuating asymmetries in adaptation capacity.

In this discourse, climate justice potentially demands a fundamental shift from only the allocation of financial resources to challenging existing structural rules rather than negotiating with them.

The Missed Opportunity: China and India’s Dual Role

Within the collective Southern strategy, India and China are the two most influential voices, yet they serve a paradoxical position. They often act through strategic and self-interested diplomacy. China’s annual $3 billion climate finance to developing nations marks a proactive leadership role, yet 96% of this is in the form of loans, less 30% is an adaptation fund, and selectively the primary focus is in the African states.

What about LDCs and SIDS? They are facing the most vulnerability. However, India’s pragmatism became more visible during the recent COP negotiation (e.g., COP28), where the BASIC bloc highly criticized Northern inaction, and Delhi did not oppose the final uneven financial package. China’s 100 small-scale projects and a $2 million fund for Pacific Island nations reveal exclusively geopolitical interests rather than climate justice.

These patterns of diplomacy make them fail to build a structural and proactive alliance within the South, where only resisting Northern agendas is not enough. What is needed is to shift toward principled and inclusive leadership; otherwise, India and China risk reinforcing the very hierarchies they claim to challenge.

Reimagining South-South Cooperation: From Solidarity to Strategy

Moving beyond symbolic solidarity and fragmented aid initiatives, the Global South requires political coherence and compatible institutional design to counter global climate injustice. If the Global South wants to shape climate governance on its own terms, it needs a transformation from developmental coordination to strategic alliance-building.

Initially, rejecting donor-recipient hierarchies, even within South, it has to institutionalize a horizontal mechanism of cooperation. A proposed South-led Climate Justice Council could be a way of coordinating adaptation finance, accounting equity benchmarks, and balancing at the negotiation table. Likewise, to ensure prosperity according to the local realities, a Climate Adaptation Technology Exchange could allow vulnerable countries to exchange low-cost, context-specific innovations without intellectual property barriers.

In parallel, the Southern countries could form Green Sovereignty Pacts to empower local ownership and autonomy by initiating climate actions within this framework, rejecting external adaptation policies that often come from political and financial conditionalities. It is timelier to become a counter-power rather than forming solely a parallel platform. Thereafter, it will be possible to rewrite the South’s voice in global climate governance.

Bangladesh and the Moral Imperative of the Margins

Bangladesh, not a geopolitical heavyweight, plays a dual role: as one of the most climate-vulnerable nations and as a vocal supporter of justice-driven climate policy. Bangladesh argued over the Loss and Damage mechanism, hosted South Asian forums to coordinate adaptation strategies, and championed the interests of CVF and LDCs. Framing climate-induced displacement as a human rights issue marks Bangladesh’s shift from reactive victimhood to normative leadership. These contributions do not call for exceptionalism; rather, these can be exemplified as moral and political importance that is embedded in many Global South countries.

This leadership often occurs in a vacuum. Bangladesh is facing an under-delivery of adaptation funding. In 2023, the UNDP reports that less than 30% of global adaptation finance reaches the vulnerable countries. Therefore, despite intellectual leadership, Bangladesh’s outcome remains stunted due to the absence of material backing from regional peers or global structures. Hence, Bangladesh could be a good reference point to understand why building a collective Global South voice is important. However, this context links vulnerability with leadership, and diplomacy with justice, where a stronger alliance is an urgent need to pressure both North and South for equitable reforms.

Justice-oriented South-South Framework

The architecture of South-South cooperation needs three main principles: climate equity, mutual accountability, and structural transformation. To resist donor-driven agendas, to ensure regional powers like China and India’s responsibilities, and to advance South-led forums for raising marginalized voices _ these three principles must be acknowledged. Maintaining solidarity within this framework is an active responsibility, especially for Southern powerful economies to advocate for vulnerable peers without reproducing Northern paternalism.

To move forward on transformative leadership and cooperation, the Global South must create a Southern Climate Justice Forum, which would operate equitable practices independently, inclusively, and freely from donor conditionalities. It would also enforce an intra-South accountability system to uphold regional power on fair responsibilities. It would establish an alternative financial model to ensure fair and equitable distribution of financial resources based on vulnerability and local priorities. Last but not least, the South should reframe cooperation as a strategic bloc-building mechanism to enhance diplomatic leverage.

Ultimately, true climate justice emerges not only by relying on the North, but also by letting the Global South lead differently, anchored in solidarity, equity, and transformation. That is the real test of climate leadership in the 21st century_ whether the Global South can lead not in reaction, but through principled transformation.

*The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of TDI.

Akash Ali

Akash Ali is an independent researcher specializing in climate diplomacy, global politics, and IR. He is currently associated with the University of Rajshahi, Bangladesh. He can be reached at akashali2000.ru@gmail.com