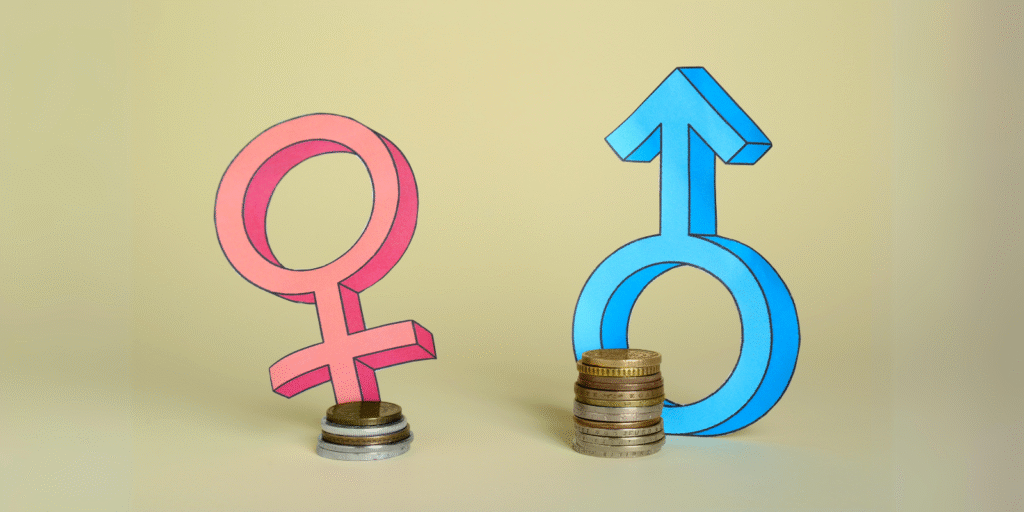

The gender pay gap in Pakistan is not just a statistic. It is a daily reality that limits the potential of women. Women earn less not because they work less but because they are valued less. This gender pay gap is a symptom of broader social, cultural, and economic inequalities that remain deeply rooted.

Despite many commitments from the government and international organizations to close this gap, progress has been slow. Recently, a government-backed report shed light on these challenges. It lays out the facts and offers a list of solutions.

The report reveals the stark reality. In 2021, only 23.2% of women in Pakistan were employed, compared to 79.2% of men. That’s a gap of over 56 percentage points and this disparity has barely shifted since 2011. These figures alone should be a wake-up call. Therefore, the report digs into why this gap still exists and suggests how to fix it.

Some of the recommendations sound promising. For example, it calls for provinces to define fair wages according to ILO standards. It suggests using gender‑neutral job evaluation tools, improving labor inspection, reforming maternity and paternity leave, and investing in better data systems. But good ideas on paper don’t always translate into action especially in a country where most women work outside the formal economy.

So the big question is: How can these policies work in practice?

Pakistan’s economy is mostly informal. Most women don’t have formal contracts, regular salaries, or access to legal protections. They work in homes, agriculture, and small workshops. In these spaces, laws – no matter how good – rarely reach them. So, while legal reform is important, laws alone won’t solve the problem.

Nevertheless, one of the report’s strongest points is its call to improve labor laws. Pakistan already has laws that promise equal pay. But these laws are rarely enforced. There are very few labor inspectors, especially in rural areas. Many women don’t even know their rights, let alone how to file complaints. Therefore, for laws to matter, institutions must be trained, funded, and held accountable. Without strong institutions to monitor and enforce rules, new policies will suffer the same fate as old ones: they will be ignored.

Another strong point in the report is wage transparency to make pay structures public. This could help uncover unfair pay practices. But again, most women work in places where there are no payroll systems, no contracts, and often no written records at all. In these settings, how can you make pay “transparent”? A more realistic idea would be to pilot this in formal sectors like banking or telecom first. Once successful, it can grow from there.

Furthermore, the report also promotes family-friendly policies like longer maternity leave and workplace childcare. These are good steps but they don’t go far enough. These benefits matter only for women in formal jobs and that is a small percentage. Plus, these policies do not challenge the basic problem that women are still expected to do most of the caregiving, whether they work outside the home or not.

The report also highlights the need for better data. Without clear data, it is hard to know where the problem is worst or if reforms are working. But again, collecting data is not enough. The data must lead to action and accountability. Civil society groups, women’s organizations, and media can play a huge role in pushing the government to act on what the data shows.

What’s missing?

However, the report misses some big points. It underestimates how deeply rooted cultural norms limit women’s ability to work. Unless we address cultural expectations like the idea that caregiving is only a woman’s job, formal benefits will only help a few women, mostly those in privileged jobs.

Think about rural areas where many women have skills, but no transport, no permission from family, or no safe space to work. Additionally, fear of harassment also keeps many women away from public life. These are not side issues as they are core to the problem. The report barely scratches the surface here.

Moreover, it also assumes that everyone like employers, local leaders, even lawmakers will welcome and support these reforms. That is unlikely. In some sectors like garments or agriculture, women’s work is undervalued by design. Employers might resist transparency and local authorities might lack interest or capacity to enforce new rules. Also, minimum wage laws often don’t reflect women’s real contributions, especially in informal work.

So, what needs to happen next?

If Pakistan is serious about change, it must go beyond legal reforms. There should be more focus on women in informal and rural areas by providing training, microloans, and platforms for selling their work. Mainly, men should also be brought into the conversation by challenging old ideas about who should earn and who should care for children.

Also, there must be a reward system by offering tax breaks or public recognition to companies that pay fairly and hire more women. Lastly, it should be necessary to track and punish non-compliance. If a public agency or company breaks the rules, they should be held accountable.

Because closing the gender pay gap in Pakistan is not just about fairness but it is key to economic progress. Ultimately, real change will only come when action replaces promises, ensuring equal pay and opportunity for every woman.

Noor ul Sabah

Noor ul Sabah is a feminist researcher focused on intersectional approaches to gender, technology, and governance. Her work explores how power and identity shape experiences of violence, migration, and citizenship.