South Asia is known for its water scarcity. In the previous century, drafts claimed the lives of millions. The next war, as said by the geopolitical experts, will not be fought over oil or gold, but water. Given the critical role water plays, its effective management can lead towards economic survival and regional stability in South Asia. Particularly, the trans-border river issues demand comprehensive understanding and water sharing agreements between the relevant actors. Conversely, disagreements and zero-sum tactics lead towards diplomatic tensions. The issue over Kabul River is a prominent example in this regard.

At Kabul River Basin, Pakistan and Afghanistan share nine rivers in total. Located at north-western Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan, the annual water flow of Kabul River crosses 22.6 billion cubic, with 20% water flows in Pakistan and the rest of 80% in Afghanistan as per the hydrological estimate. Moreover, Kabul River sprawls over 700km.

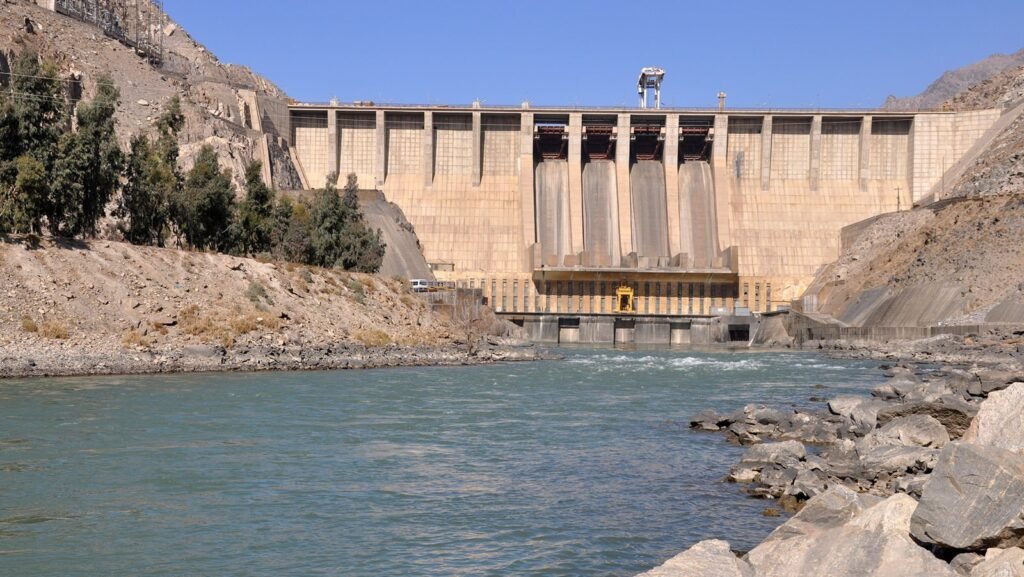

With the capacity to generate 3100 megawatt of electricity, it is the most significant source of hydro-energy for land-locked Afghanistan. Based on its position, it is divided into two: Upper and lower riparian states. The river pattern in Pakistan follows the lateral symmetry. This is the point where the issue starts.

Despite being a lower riparian, Pakistan consumes around 90% of the water as there is no infrastructure or dams on the Afghanistan’s side. Afghanistan uses this water for non-strategic purpose (e.g., drinking mainly) while Pakistan use it for the strategic purpose (e.g., agricultural use in KPK). Interestingly, Pakistan and Afghanistan both are not a signatory of UN Watercourses convention. Yet, some conventions directly applies on both given their customary status. These include UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and Convention on Biodiversity.

Read More: The Hague Court Shatters India’s Attempt to Suspend IWT

Given the non-signatory status and no bilateral agreement, traditional issues between both states—such as refugee issue, TTP hideouts, and Afghanistan as a proxy ground—negatively spillover into non-traditional security domain. Sometimes, Afghanistan threaten to cutoff the water supply of Kabul River for Pakistan. Even it objected the construction of Dasu Dam that is situated 100-200 km away from Kabul River. Not only with Pakistan, had the interim government also weaponized water issue with other regional states such as Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan.

Multiple efforts are made in the past to discuss the policy options to reach an agreement over water sharing between Pakistan and Afghanistan. For instance, Pakistan has offered negotiations, water sharing formula, capacity building support, and the technical help to resolve the paradox. On the other side, different Afghan governments also suggested dialogues to discuss the issues. Yet, no progress has witnessed for amicable water sharing mechanism. The politicizing of water has complicated the efforts.

Why the Issue Persists?

Durand Line

Durant Line is one of the major hindrance in the Pak-Afghan relations. From the perspective of Pakistan, it is an international border. The same perception exists world-wide. However, the Political Expansionist Nationalism (PEN) dominates the thought process of policy makers in Kabul.

A decree was issued during Karzai’s government to call and write the Pak-Afghan border as Durand line instead of international border. Durand Line has been the tool of Afghanistan’s foreign policy throughout the history.

As the rivers pass through this particular line, any potential water sharing agreement would weaken the pre-colonial claims of Afghanistan over the so called Durand Line. This is the major hurdle in the negotiations process.

Mistrust

Historically, Pakistan has been a major ally of Taliban’s regime. It supported Taliban against Soviet Invasion under Brezhnev Doctrine. Pakistan was among the few states which accepted Taliban’ government in early 1990s.

However, Pakistan’s alignment with the United States, while maintaining the ties with Taliban at the same time, created a distrust between Taliban and Pakistan.

After the U.S. withdrawal, Taliban are in power, it is unlikely that Afghanistan will trust Islamabad again. This is another major hurdle in the resolution of water dispute despite attractive offers from Islamabad.

Misperception

Nowadays, everywhere in the world, water has become a source of contention. States are exerting the logic of absolute territorial sovereignty. Even there are disputes in the intra-provincial water sharing agreements.

When it comes to sharing water with the neighboring state, the matter becomes more intensive. Given the geopolitical ambitions and zero-sum game, with a view that other should get the least benefits from the deals, the peaceful settlement of the water related issues is unlikely between Pakistan and Afghanistan unless a charming offer is being made from the opponent side.

Pakistan has already offered a support in the constructions of dam, capacity building, information sharing, and research. Above all, Pakistan proposed 80-20 per cent water sharing formula with the previous governments of Afghanistan. Yet, the strategic ambiguity by Kabul persists in this regard.

Lack of Political Will

Like many other issues with Afghanistan, this issues is also of a political nature, with both sides unwilling to reach an agreement. From the perspective of Kabul, Afghanistan is already benefiting from the river water and no issue has been created by Islamabad so far.

Initiating a negotiations with Islamabad will weaken the assertive position of Afghanistan. In contrast, Pakistan is trying to institutionalize the water sharing mechanism given the climate change, water shortage and political involvement of India.

If prioritized, this issue can also be resolved with the mutual political consent.

Broader Regional Factors

Excessive involvement of India in Afghanistan, particularly in the recent years, has deteriorated Pakistan’s ties with Kabul. Afghanistan is being used as a proxy ground by New Delhi to spread terrorism and inflict a proxy warfare against Pakistan.

In response, Pakistan started deporting Afghani migrants back to Afghanistan, creating a huge demographic pressure on the war-torn Afghanistan. This move has economic and political implications. Economically, the interim Afghan government is unable to support 3 million deported refuges, creating an anger and distrust against Islamabad.

India has utilized this opportunity to deviate the public opinion in Afghanistan. Any agreement with pro-Pakistani stands is unlikely to be supported by the locals. This paradox has made the possibility of any agreement in the short-term unlikely.

Read More: Game-Changer: Pakistan, China Extend CPEC to Afghanistan

Way Forward

CPEC Extension: Although distrust and historical animosity existed between Pakistan and Afghanistan for decades now, the evolving geopolitical scenario—particularly informal trilateral summit between Pakistan, Afghanistan, and China—forecast promising outcome. Recently, China and Pakistan officially invited Afghanistan to join CPEC. In this scenario, establishing peace and avoiding historical mistakes become a need of the time in order to gain the maximum benefits from the regional connectivity projects.

China’s Mediation: Apart from direct dialogues and trust building measures, both parties must request China to mediate into this issue in order to reach a win-win solution. Beijing’s image is positive in both countries and it possess the necessary technical and operational capabilities to resolve the due issue. Moreover, China’s mediation will help gain funds and loans for the completion of dams and infrastructure projects on the Afghanistan’s side as the interim government lacks the required capabilities.

Joint Commission: As the issue is more of a narrative than practical, a joint commission must be formed on the immediate basis. It must include the stakeholders from both sides. It will help maintain a timely communication, management of the seasonal water, cooperation in technical domain, and infrastructure buildup at Shatoot and Kama Dam. Apart from that, a research wing should be established that could bring the gap between the theory and practice, ultimately resulting in a positive outcome.

Is a Neutral Mediator feasible?

Given the hardcore interpretation of Islamic governance, it is unlikely that international bodies such as World Bank or the United Nations will mediate into the matter. But, in a long-term process, if the restriction against women and girls got relaxed, there are chances that a mutually agreed treaty will be reached between Pakistan and Afghanistan—modeled after Indus Water Treaty.

Moreover, to gain technical and financial support from the international institutions, Taliban regime can incorporate Sustainable Development Goals (SGDs) into governance. This step would help align water saving and capacity building on Kabul River with the goals of the United Nations, ultimately facilitating broader support and help.

Dispute over water sharing mechanism on Kabul River is the historical issues persisted between Pakistan and Afghanistan, hindering political cooperation and impeding distrust between the neighbors. Given the changing regional geopolitical landscape, it is the right time to sit together and resolve the issue bilaterally or with the help of neutral third party mediation.

Muhammad Abdullah

Muhammad Abdullah is a final year student of International Relations at School of Politics and International Relations (SPIR), QAU. He can be reached at muhammadabdullahhaf235@gmail.

- Muhammad Abdullah