Some women vanish like whispers,

Unheard and unseen in their need.

Yet the world still feasts on their silent screams.

(Sabah, 2025)

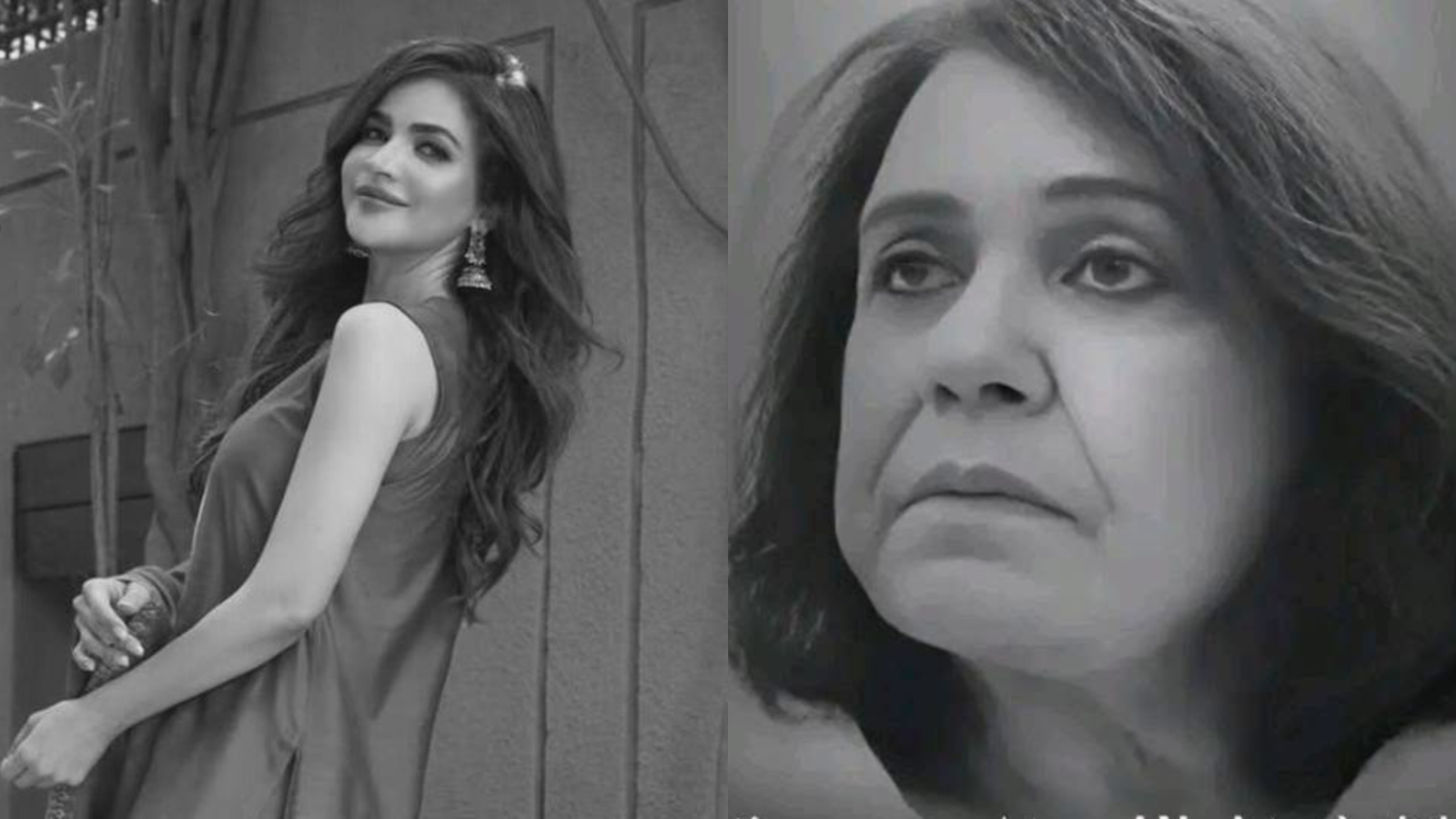

Earlier this year, Pakistan witnessed two hauntingly similar deaths in showbiz industry. One was senior actress Ayesha Khan, who was discovered lifeless in her home a week after her death. The second was Humaira Asghar Ali, a model and an actor, who was discovered decomposing in her Karachi apartment. Early forensics suggest she died months ago.

In both cases, there was no knock on the door, no voice calling to see how they were, and no human touch of solicitude. These women had disappeared long before their deaths, socially eradicated even as their bodies rotted away. But as soon as their deaths were discovered, social media erupted. With graphic images, viral videos, and speculative threads along with moral policing masquerading as concern.

Their corpses became hashtags, their lives posthumously hyper-analyzed by strangers who had ignored them in life.

This is the grotesque rhythm of our time: the digital feast upon the dead. Why were their bodies used for postmortem scrutiny online instead of treated with dignity by relevant authorities?

This article examines the hypocrisy of national sentiment in Pakistan which serves more as performance than care. It interrogates why women’s deaths through media, clicks, and online attention are monetized? Drawing on Sara Ahmed’s The Cultural Politics of Emotion (2004), I argue that the capitalist and patriarchal system consumes women even in death.

When Ayesha died, a digital swarm of emotions cursed her children for neglect. When Humaira died, she was cursed for being a daughter who had apparently cut ties with her family.

Ayesha’s motherhood was weaponized against her kids. Humaira’s independence was weaponized against her legacy. In both cases, the public refused to reckon with systemic isolation, instead falling back on moral policing: why didn’t her family check on her? Why did she live alone? How did she die without anyone noticing?

No one asked the more honest question: Why do we let our women disappear until they are no longer useful, visible, or productive?

As a woman, if you stay in the home, you are devalued and blamed. If you leave, you are punished by abandonment.

Digital mourning as performance

Sara Ahmed (2004) has long argued that public emotions do political work. The grief over these deaths which is expressed online does not necessarily reflect care. Instead, it reproduces a national image of concern that allows users to feel morally good while upholding a status quo that caused the very abandonment they lament.

This is a form of emotional capitalism: a performance of care that conveniently replaces action. Sharing a viral tweet about checking on loved ones doesn’t actually rebuild relationships. Posting heartbroken emojis under videos of decayed bodies doesn’t undo decades of isolation. Emotions can be mobilized to mask inaction or even to justify complicity. You suggest that digital grief becomes a way to feel morally righteous while ignoring the very structures that isolated these women in life.

And the worst? Many of these expressions are laced with misogyny. Some claimed Humaira deserved it. Others said her life was ‘immoral’. Many cloaked their judgment in concern that women who leave family end up like this. Hence, grief, blame, and concern get selectively attached to women’s bodies.

Society mourns just enough to reinforce norms (e.g., the obedient daughter) not to interrogate why women are punished for autonomy.

This is not mourning. This is monetization.

Social media turns suffering into content. Traumatic moments become spectacles. Deaths, particularly of women are hashtagged and algorithmically circulated for engagement. The woman’s body is no longer her own but it belongs to the feed.

In both Humaira and Ayesha’s cases, strangers dissected their lives and deaths as if performing a forensic analysis. Photos of Humaira’s rotting body and abandoned room were shared across platforms. There was no consent, no dignity but only the viral potential of a tragic image.

This isn’t an anomaly. It is a system that values women’s pain only when it sells.

A capitalist system that erases connection

In a capitalist system, people are often treated less as human beings because the relentless pressure to compete, produce, and succeed leaves little room for care, connection, or community. This isolation doesn’t arise from a lack of compassion but from a structure that actively discourages empathy. Because we are told to hustle but not to pause.

Whether rich or poor, the pressure to appear fine overrides the reality of isolation. Research shows that women in Pakistan face disproportionately higher risks of social isolation and mental health issues due to patriarchal restrictions and economic dependence. Therefore, feeling sorry for a woman after her death is not the same as caring for her in life.

We are not failing to feel, rather we are failing to act.

We share stories but do not change behaviors. We comment with sorrow but do not visit our own neighbors.

What we need is not more digital mourning, but:

- Mental health access for all, especially isolated women

- Legal recognition and protection for women estranged from families

- Community-based outreach and check-in systems, especially for aging or single women

- Media ethics that prohibit the sharing of graphic images

This is how we move beyond temporary outrage and hashtags. This is how we build solidarity.

Soon, Humaira will be forgotten. Her name will disappear under newer trends. Ayesha’s story will become a cautionary tale which will be used to scare women into obedience. And the world will move on, feasting on the next silent scream.

So I ask you: When a woman dies alone, who do we really mourn? Her, or our own complicity?

Noor ul Sabah

Noor ul Sabah is a feminist researcher focused on intersectional approaches to gender, technology, and governance. Her work explores how power and identity shape experiences of violence, migration, and citizenship.