Officials in Copenhagen confront an uncomfortable question, how secure is sovereignty when it can be casually discussed as a transaction? At the same time Middle Eastern diplomats explore the new “board of peace” championed not by any institution, but a single political figure, Europeans quietly worry about alliance commitments, while the rivals observe these cracks with interest.

These developments are not random, in fact connected, as they reflect a deeper transformation in global politics, one where peace is not guaranteed by rules, institutions, or shared norms, but instead negotiated through deals, leverage, and personalities. This is the politics of brokerage, which is reshaping the contemporary global order.

Peace in the post-Cold War era was framed as a collective responsibility. International institutions, however imperfect, claimed authority over conflict management. Treaties mattered, alliances signaled credibility. Importantly, sovereignty was treated as a fixed principle, not a bargaining chip.

That framework is eroding. President Trump’s proposed “Board of Peace” reflects this shift. Unlike traditional multilateral mechanisms, this initiative places decision making power in informal, personalized hands. Peace in this model will not require consensus or law, but negotiations, pressure, and deal making.

The appeal of this approach is in its speed and decisiveness. As supporters argue, institutions have failed, they’re slow, politicized, and ineffective in enforcement. Critics counter the idea of personalized authority as it can destabilize the international order. But what matters is the precedent being set, peace is becoming transactional.

European reluctance towards such an initiative stem from its deeply institutional architecture. NATO, the EU, and international law remain central to its political identity. Trump’s past skepticism toward NATO and his remarks questioning alliance obligations have already unsettled European capitals.

Middle Eastern states, however, sees it differently. They have navigated power politics without institutional protection for quite long. For them, proximity to influence matters more than process. A brokered peace, even if informal, may appear more practical than distant multilateral promises.

The credibility of the “Board of Peace” will be ultimately determined in Palestine. No conflict better illustrates the test between brokerage and justice. For decades, Palestinian aspirations have been associated with international institutions, UN resolutions, peace conferences, and diplomatic frameworks promising a rule-based outcome. The proposed brokerage political model claims to bypass this paralysis. Yet the question remains: bypass in whose favor?

A broker-led peace model prioritizes leverage over legality. In such systems, outcomes depend on bargaining power. Israel enters negotiations as a militarily dominant, economically strong, and diplomatically influential actor. Palestinians, on the other hand are fragmented politically and territorially and possess limited leverage.

Moreover, Trump’s earlier approach to the Palestinian question, recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, sidelining Palestinian leadership, and the Abraham Accords, demonstrates how brokerage can produce agreements without resolving core disputes. Regional normalization may advance, but Palestinian statehood moved further from reach.

Under this board of peace, Palestinians risk becoming observers rather than participants, and peace may be negotiated around them rather than with them. This is the fundamental flaw of the brokerage model, it can manage conflicts but struggles to provide lasting resolution.

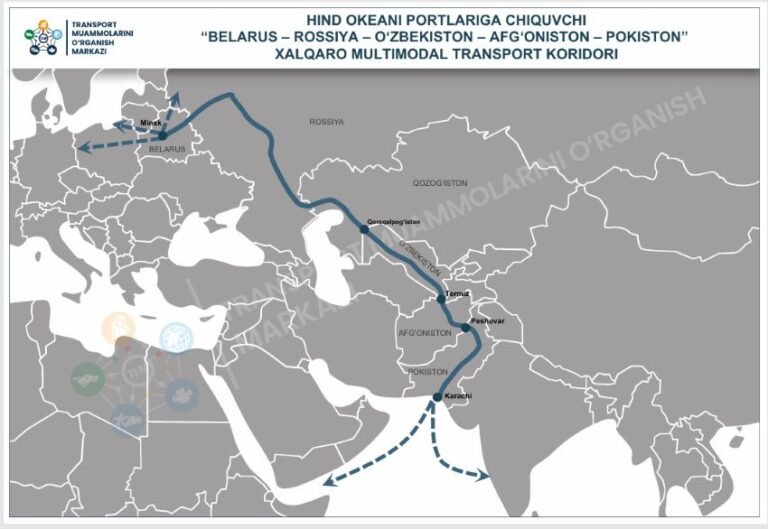

For Pakistan, these circumstances are not unfamiliar. Islamabad from a long time has experienced the limits of international institutions, particularly on issues like Kashmir. A world governed by power rather than principle is not new. What is new is its normalization.

Pakistan in this brokerage political model must adapt without illusion. Moral arguments alone cannot be substantial. Simultaneously, overreliance on powerful intermediaries can risk strategic vulnerabilities. The challenge lies in balanced engagement with emerging power brokers while preserving strategic autonomy.

When peace becomes a deal, it may still be peace, but it is fragile, reversible, and conditional. The Board of Peace is not merely a proposal, it is a symbol of a world where stability is negotiated, not guaranteed.

That is the politics of brokerage. And it defines the age of global disorder we are learning to live in.

*The views presented in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Diplomatic Insight.

Abdul Momin Rasul is a contributing author on TDI

- Abdul Momin Rasul

- Abdul Momin Rasul

- Abdul Momin Rasul

- Abdul Momin Rasul