Deborah Melom Ndjerareou

Recent turmoil in the relations between France and Sahelian countries such as Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger is reshaping how the French state relates to its former colonies. Youth activism in the Sahel region has played a role in questioning France’s traditional relations with these countries, and vocalizing these concerns has led to significant political and social changes.

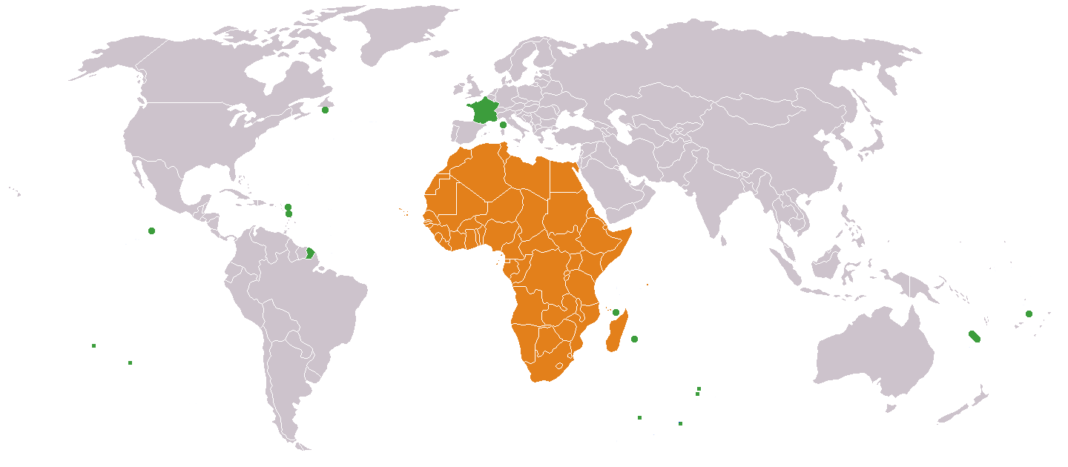

In the 1960s, African countries under French colonial rule began to gain their independence and entered an era of relative “freedom.” France maintained close political and diplomatic ties with its former colonies, which have been ever-evolving and a subject of international debate. The nature of the relationship presents connotations of dominance and the idea of a sphere of influence. This dynamic is illustrated by the Françafrique concept, which literally means French post-colonial domination.

French foreign policy discourse on the continent of Africa varies from one region to another, and Françafrique is more pronounced in former colonies. France enjoys a “privileged relation” with these former colonies and has a strong presence in the Sahel region with an agenda to fight against terrorism. This region comprises ten countries, 90% former French colonies.

In the last seven years, various countries in the Sahel region have seen regime changes in which France has been involved at the diplomatic and military levels leading to an outcry of French involvement in Sahelian internal politics.

President Emmanuel Macron, during his first term, attempted to shift France’s foreign policy approach in francophone Africa, especially in the Sahel region. The president pushed forth the idea of reforming diplomatic and political relations, emphasizing the message of renewed relationships in the post-colonial era. He cites his birth after the colonial period as a reason for his interest in proposing renewed cooperation.

In these theoretical reform propositions, France has maintained a physical presence in the Sahel region through military troops in Chad, Mali and Niger and Burkina Faso. These troops are present to fight terrorism in the region but have created a contentious response from the populations, especially the youth.

The organization of the annual Africa-France forum in October 2021 shifted from gathering high-level politicians to focusing on dialogue with African youth activism movements, civil society organizations, and key foreign policy officials. In response to these reform attempts, there has been a rise in civil society organizations, especially among youth activism movements denouncing the French state. It is important to note that the makeup of these movements is mainly youth aged 18-35, who are citizens born after the colonization period.

Youth movements in Sahelian countries such as Chad, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Senegal have been vocal in their opinions. The visual and verbal anti-French sentiment was pronounced and noticeable through street protests, social media campaigns, and political support to leaders who embodied their thoughts. During street protests, for example, French establishments have been targeted and destroyed in all the countries mentioned.

In a 2020 report published by the Ichikowitz Family Foundation, based on a survey of over 4,500 youth (aged 18-24) in sub-Saharan Africa, there are negative views of France’s influence in its former colonies. 71% in Gabon, 68% in Senegal, and 60% in Mali hold this negative opinion. This sentiment has existed prior to President Macron’s election; however, in the past seven years, it has been on the rise. In the Sahelian countries, the presence of French troops with a mandate to fight terrorism, and French intervention in national politics, have exacerbated this feeling. The wave of protests has always been in response to these events and is most notable in Mali, Chad, and Senegal.

In December 2019, anti-French protesters took to the streets brandishing signs saying, “Non au néocolonialisme français” meaning no to French neo-colonialism, “Macron missionnaire de la Françafrique” meaning Macron, advocate of the Françafrique, and “Non à la France” meaning No to France. In January 2020, during a protest in the Malian capital Bamako, over 1,000 young people gathered and brandished signs saying, “A bas la France” meaning Down with France, and “France Dégage” meaning France get out. In these protests, French establishments were destroyed, and the French flag was burned.

In an article on anti-French sentiments, a participant in the protest in Mali stated: “It is not against the French people that we are angry but against the policy of their state” (translated from French). This quote is important in illustrating that the negative sentiment on the rise is towards the state of France and its policies and not towards French citizens. This is an important component in the analysis of this sentiment, especially in the Sahel region which has a high number of French citizen residents.

The age of agitation in the continent of Africa has increased the youth’s desire to be part of the governance of their countries. In the Sahel region, the wave of outrage and protests in the streets demanding inclusion from local governments and opposing the involvement of foreign ones is a phenomenon worth noticing and analyzing. With 60% of the population being under the age of 30, the trend is the reimagination of political trends, a reassessment of the past, and using new methods to ask for reforms. The Sahelian youth is demanding more inclusion and accountability from their government and pushing back the French state’s approaches in the political and diplomatic affairs in the region.

President Macron’s first term was underlined with the narrative of renewed relations moving away from the colonial past and placing the youth at the center of France-Africa relations. To achieve this, France increased development funding and created new initiatives for the youth on the continent. What the approach failed to accomplish was convincing the youth that France-Africa relations (in the Sahel region) were changing.

The triangular power and communication dynamics between the State of France, African states, and the African population is key in understanding that President Macron’s reform narrative is no more than a discourse that has not materialized in the first term. The attempt to create a direct connection with the youth without involving heads of state; the youth reproach their leaders of not including them in governance and accusing the state of France of supporting oppressing regimes creates a tumultuous dynamic in which the reform in the French discourse is impracticable.

The youth’s reaction to this French foreign policy has implications related to the overall political stability of the region. It is transforming the future of France-Africa relations and the French presence in the Sahel. The observed response in the chosen time frame is “No” to France’s interference in national politics, the backing of oppressive governments, and support for an unconstitutional power grab.

*The author is a humanitarian from Chad and holds extensive global experience with the United Nations and NGOs across various regions. With degrees in language studies and International Affairs, she is fluent in English, French, Spanish, and her native Ngambaye. Passionate about African affairs and languages, she combines her expertise to make a difference worldwide.

**The opinions in this article are the author’s own and may not represent the views of The Diplomatic Insight. The organization does not endorse or assume responsibility for the content.

The Diplomatic Insight is a digital and print magazine focusing on diplomacy, defense, and development publishing since 2009.